16. Palace of Niccolò Grimaldi

25 March 2022

18. Palace of Luca Grimaldi

25 March 2022This palace was one of the first in the street to be built (1562) and was commissioned from Giovanni Ponzello by Baldassare Lomellini. lt then passed to the Salvago family (1588), who kept it until it was acquired by Cristoforo Spinola, the Republic’s ambassador in Paris ( 1770 ). The Spinola family made radical alterations in the Neodassical style. The work was originally entrusted to Charles de Wailly, the architect to the king of France, but he quickly

handed it over to the Genoese Emanuele Andrea Tagliafichi (cf. in Rubens, 1652 ed., XI, Palazzo del sig. Henrico Salvago). The building was bought in 1778 by Domenico Serra and in 1917 it passed to the Campanella family. As in the case of Palazzo Doria/Tursi, built just after, the courtyard is considerably higher than the entrance hall, to which it was connected by a staircase. The alterations in the 18th century led to the two areas being separated by a wall.

Aerial bombardment in I942 severely damaged the main hall, the loggia and the oval dining room; only a ceiling with fresco decorations depicting “Dido and Aeneas” by Gio. Batta Castello and stuccos on the west wall remain of the original decorations on the piano nobile. The first floor includes rooms not affected by the 18th century modifications, including

one with “Roman scenes” by Andrea Semino. The portal by Taddeo Cariane bears the inscription VENTURI NON IMMEMOR AEVI.

Few palaces in “Strada Nuova”, like this one at civic number 12, can boast of an ideal kinematic sequence of drawings, important sceneries, photographic documentations which through the centuries have restored its tormented stylistic course.

The first exposure can only be imagined, on the basis of a planimetry of the area acquired on the south side by the magnificent Baldassarre Lomellino. It is 1563, and with the usual coming and going of suppliers and mule-drivers the first building of the second stretch of the street had started, while the first stretch still suffered from the emptiness of two unbuilt areas and started – as we have already seen – two simultaneous building sites.

The master builder was engaged in taking measurements for the supply of Promontory and Lavagna stones and from Finale rustic ashlars, weighting their quality and price, and in evaluating old houses to be demolished to make space for the garden. Everything was documented until 1566 when the building was finished with the name of the architect Giovanni Ponzello, already singled out for the project of the palace of Angelo Giovanni Spinola. Younger than Bernardino Cantone and destined to inherit his rôle of Chamber architect (1576), he was now the absolute protagonist of the second part of the undertaking, at least for this end of the century.

From what we know he must have satisfied his client who, being already aged and interested in reducing times, immediately provided for the decoration of the new palace and made his will. And here is the second image showing us this Magnificent Baldassarre Lomellino portrayed in a statue which, owing to his generous bequests, he deserved in the room of the Congregations in Palazzo San Giorgio. The great flow of financial investments between Genoa and Spain, where he deftly navigated, kept him away; all things considered the new dwelling was only a status symbol and in 1578 he was persuaded to sell it. Finally the drawings by Rubens – third picture in 1622 – show what Ponzello had created, without usurping the word, to this palace now belonging to the Salvago family.

The proportions, rigorously in the Alessi style with three central axes, and lateral avant-corps of one axis were organized in a vertical system with a small mirador loggia on the top of the roof which seemed to correspond to a whim of the landlord. A high rustic plinth and the ashlar frames of the avant-corps completed the work in a perfect design.

The newness was inside, where the decorator had decided to give a vertical perspective to the entrance of this dwelling which being situated on the downhill side had no problems of embankments to be climbed. The central staircase created a real scenery connecting the entrance-hall to the loggia looking onto the garden, elevated in correspondence with a floor of rooms and drawingrooms.

In the basement, which in this case cannot be considered so, there must have been, as usual, rooms for stableboys and servants. We can see them at work looking out of the oval windows, saddling horses, enjoying the commotion of the farewells between the lord in his robe on the doorsteps, and the young son who, with his train, leaves for a long journey, while his mother wipes her tears. This very crowded scene had been sketched with a Flemish skill by Cornelio de Wael for a print of the series The Prodigal Son, depicting The Departure, without breaking away from what seemed a real and also usual episode. It is the fourth image, more or less contemporary with those by Rubens, which sliding onto our imaginary screen allows the setting of the classical portal with stucco puttoes holding garlands, still very well kept, and the crescentshaped paggiolo, a very small spare area now behind the times. In 1770 the palace passed into Cristoforo Spinola’s hands; he was already ambassador in Paris, and he did not miss the opportunity of realizing a memorable decorative undertaking. The neoclassical appearance given to the interior was entrusted to Andrea Tagliafichi, a refined Genoese architect, less known – even then – than what he deserved.

In the restructuring of the grand hall he is only the executor of a regal project, the work of the French artist de Wailly, in which an imposing corinthian order on the wall was enriched with friezes, paintings, mirrors, crystals and lapislazuli and we must believe Federico Alizeri, the most famous art chronicler of Genoa’s history, when he said “that the plentiness of matter was in competition with the gentleness of shapes”. The engravings of Jean Louis Desprez help us as they represent planimetry, vault, section and perspective view of the “Salone del Sole”, as it has always been called.

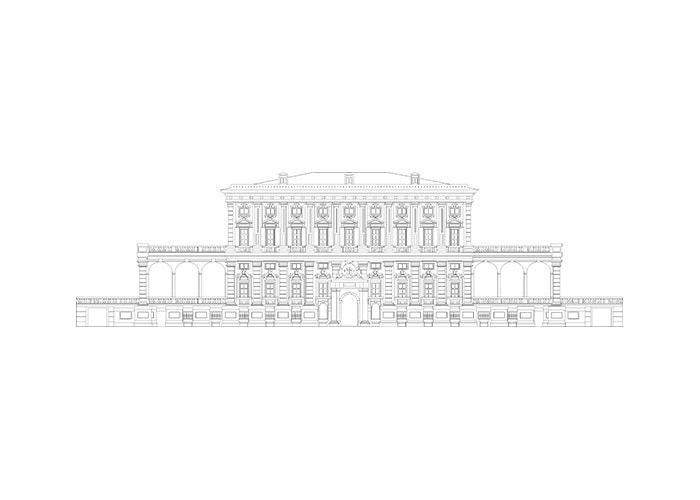

The drawings of Gauthier also illustrated the other transformations made by Tagliafichi: the garden replaced by a porticoed courtyard supporting a terrace with neoclassical pavilions to the level of the “piano nobile”, the new polygonal arrangement of the entrance-hall enclosed by a small gallery with a laterally developed staircase and the façade, no longer divided into three, horizontally opened with seven axes of windows. At that time the owner of such a regal pomp was Domenico Serra who did not modify anything, like the Campanella family, the owners since 1917. Unfortunately the war events came with the bombardment of October 1942, much more devastating than the bombs of Louis XIV, to deprive the palace of its most famous title of glory.

The dramatic photographs of the building torn apart from top to bottom in its central part should be the last image of our sequence; we prefer to replace it with the miracle of rebuilding and of the salvage of those sixteenth century frescoes left or destroyed by the eighteenth century decoration. It was not by pure chance that Baldassarre Lomellino ensured himself the best names in the fresco field (from Luca Cambiaso – The Council of the Gods, lost – to Andrea Semino – Roman Tales in two drawing-rooms – and Giambattista Castello, with his Histories of Aeneas framed in plastic hermae), on the point of leaving for Spain from “Strada Nuova” and from the city which gave him more opportunities than glory.

Updated bibliography post 1998

E. Poleggi, L’invenzione dei Rolli, catalogo della mostra, Genova 2004.

M. Spesso, L’architettura a Genova nell’età dell’Illuminismo, Pisa 2007

The texts have been updated thanks to the INSIDE STORIES project financed with funds - Law no. 77 of 20 February 2006 "Special measures for the protection and enjoyment of Italian sites of cultural, landscape and environmental interest, included in the "World Heritage List", under the protection of UNESCO.